Markets

Local: The ASX200 declined by -0.1% in October. As the Australian market lags in its pricing of higher-than-expected inflation and tightening monetary policies.

Global: The S&P500 index climbed 7.0% in October after a strong US earnings season.

Gold: Gold prices rose $26 to $1,769 per ounce.

Iron Ore: Iron Ore dipped $3 to $108 per metric ton as China`s industrial production growth slowed.

Oil: Oil climbed $6 to $84 per barrel a key factor on increasing inflationary worries.

Property

Housing: Australian housing values rose 1.5% in October, a similar result to August and September. However, taking the monthly change out another decimal point shows the market is continuing to slowly lose momentum since moving through a peak monthly rate of growth in March (2.8%). Nationally, the monthly growth rate eased to 1.49% in October from 1.51% in the previous month.

CoreLogic’s research director, Tim Lawless, says housing prices continue to outpace wages by a ratio of about 12:1. This is one of the reasons why first home buyers are becoming a progressively smaller component of housing demand. New listings have surged by 47% since the recent low in September and housing focused stimulus such as HomeBuilder and stamp duty concessions have now expired. Combining these factors with the subtle tightening of credit assessments set for November 1, and it’s highly likely the housing market will continue to gradually lose momentum.

Economy

Interest Rates: RBA Cash rate remained unchanged at 0.10%. With rate rises looking to come in late 2023.

Retail Sales: Retail sales rose 1.3% in September. The first monthly rise since May 2021, following falls of 1.7% in August and 2.7% in July. Mainly due to the Delta outbreak.

Consumer Price Index (CPI): The Consumer Price Index rose 0.8% this quarter. Over the twelve months to the September 2021 quarter, the CPI rose 3.0%.

Agriculture: The value of crop production is forecast to increase by 7% in 2021-2022 to a record $39.5 billion because of strong price increases for grains, cotton, and sugar. The value of livestock production is forecast to increase by 8% to $33.5 billion, driven by higher volumes. This is a $8.0 billion upward revision from the outlook issued in June, and the largest upgrade in a single quarter in at least 20 years.

Bond Yields: Australian government 10-year bond yields rose 69bps to 2.08%. The US 10-year treasury bond also rose to 1.594%

Exchange Rate: The Aussie dollar rose slightly against both the American dollar and the Euro, at $0.754 and $0.649 respectively.

Consumer Confidence: The Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index of Consumer Sentiment for Australia fell by 1.5% mom to 104.6 in October 2021, as worries over the longer-term outlook for the economy overshadowed relief from the loosening of COVID-19 restrictions. The economic conditions in the next 5 years dropped 5.6 percent to 108.1 and those in the next 12 months were down 1.7 percent to 103.2.

Employment: The national unemployment rate edged up to 4.6 per cent, from 4.5 per cent, with another dramatic deterioration in the participation rate the main reason why the unemployment rate did not jump further. The participation rate hit a 15-month low, with just 64.5 per cent of people aged 15 and over currently working or actively looking for work.

UK Employment: The UK unemployment rate was estimated at 4.5%, 0.5 percentage points higher than before the pandemic, but 0.4 percentage points lower than the previous quarter.

Purchasing Managers Index: The Australian Industry Group Australian Performance of Manufacturing Index (Australian PMI®) eased by 0.8 points to 50.4 points, indicating no improvement in average activity levels across manufacturing in October (seas. adj). This was the fourth consecutive month of deceleration and the weakest monthly result for the Australian PMI® since September 2020. Results above 50 points indicate expansion, with higher results indicating a faster rate of expansion.

Covid: Vaccination rates locally continue to rise especially in NSW with over 93% of eligible people receiving at least one dose of the vaccine and over 88% have received both doses. Globally 3.06 billion are fully vaccinated around 40% of the global population.

Sources: ABS, AFR, CoreLogic, NSW Health, Deloitte Access Economics, Macquarie MWM Research, RBA, UBS

Comments

What will kill our house price boom?

Sydney’s median house price is close to a record-breaking $1.5 million, as the Australian property market continues to boom during the COVID pandemic. With the RBA sticking to their 2-3% inflation target as the key driver to any cash rate change; it would be smart to assess the inflationary pressures the economy is starting to see.

The September quarter inflation reading was surprisingly high and has some economists (however unlikely) predicting up to three interest rate rises next year, this could finally see the record breaking house price boom on its last legs. The most significant price rises in the September quarter can be seen from new dwellings (+3.3%) and oil (+7.1%) with extreme changes like this the RBA may need to retract on its promise that interest rates will not rise until 2024. Other reasons for the house price surge can be less exciting, the implications of COVID have stopped people travelling not only overseas but also interstate as well as the shutting of clubs, pubs and restaurants giving people extra disposable income they may not have had prior. Meaning that homeowners are putting spare cash normally spent on travel into their home. This could partially explain the high level of demand for property over the past year or two as people are fast tracking their property decisions. Furthermore, due to interest rates being at an all-time low homeowners are able to leverage up the amount of debt they can accrue due to the low interest repayments. Credit growth lifted 0.9% in June, well above market consensus of 0.4%, driven primarily by business lending (up 1.6%), with the annualised growth rate now running at 4.5%. All contributory factors to inflationary pressure.

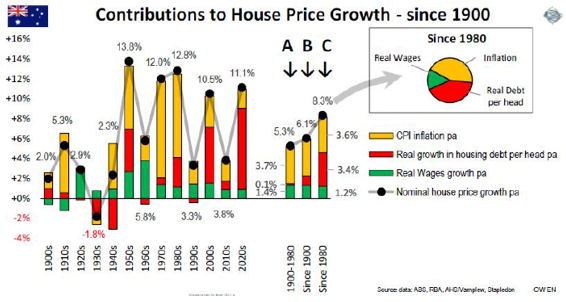

Contributions to house price growth can normally be separated into three economic fundamentals.

- Real wages growth

- Real growth in housing debt

- CPI inflation

One of the biggest influencers to house price growth especially in the last 10 years is the amount of housing debt per head which can be directly attributed to the low interest environment. The growth in the housing sector has led to Australian banks growing their loan sheets, with home mortgages accounting for 60% of total bank lending. With higher levels of household debt, mortgage owners will be more and more susceptible to any sort of economic shock. If households are constrained, in the sense that they do not have a great deal of income left after meeting their debt obligations, they are more likely to reduce consumption and in turn will amplify the impact of an economic shock.

Another point to highlight is Australia`s ability to have economic growth move at a strong pace without generating excessive wage costs. By itself, declining real wage cost should reduce the rate of real house price growth as generally people have less money to spend, but this has been more than offset by the dramatic rise in housing debt. The red bar in column C shows that real level of housing debt per person has increased by 3.4% pa above inflation a faster rate than at any other period in history.

Part of the reason for house price rises was from the low supply of homes due to the lockdowns, this problem is now likely to end with the re-opening of the economy, this in hand with being allowed to travel could reduce our obsession with property. On top of that, APRA is telling banks to make it harder for their prospective borrowers. Currently new variable home loans are typically offered something close to 2.8%. The new requirement will prevent lenders from offering such a loan unless the borrower can cope with an increase to 5.8%.

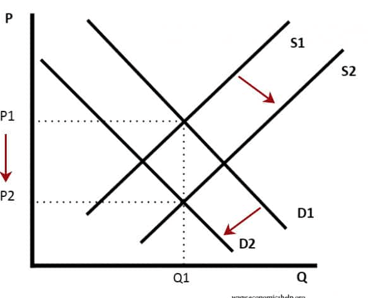

The graph above shows simply how all these factors could impact house prices, an increase in the supply of homes from S1 – S2 and a decrease in the demand of homes from D1-D2 could introduce a significant fall in house prices from P1-P2 in years to come.

The existential question is where the RBA and the US Federal Reserve’s “neutral” cash rates lie. Most economists think the local neutral rate is between 2 – 4%. If this is correct, it would mean that the RBA has to raise the cash rate to about 3% to ensure it is neither contractionary nor stimulatory. Many would say however that the neutral rate is a lot lower than people think, and closer to 1 – 1.5%. It’s ultimately an empirical question.

Even 100 basis points of increases would have profound consequences for asset pricing. Combined with some out-of-cycle rises from banks courtesy of normalising funding costs, this would probably force house prices, for example, to correct about 15 – 25%. In fact, the RBA’s own house price forecasting model implies a larger drawdown of about 33%.

In the decade since the global financial crisis, central banks have been able to pour seemingly infinite amounts of money on all economic problems because there have been no inflationary costs. It has long been argued that these policies will prove inflationary. Central banks increasingly face that invidious choice that their predecessors confronted decades ago: do you want higher growth or lower inflation in a climate in which inflation expectations are climbing?

With the consequence of core inflation moving into the RBA`s target band of 2-3% it is likely that the cash rate will most likely increase late 2022 or early 2023 to somewhat offset the increases we are bound to see on inflation.

Sources: ABS, AFR, Capital, RBA

How Sustainable is Australia’s Economy

In a time of serious change there does not seem to be a better opportunity than now for Australia to modernise its economy and pursue a more economically sophisticated future post Covid-19. You might be wondering why we need to pursue such an ambitious goal, but the data may surprise you.

It is safe to say that the Australian economy has defied expectations over the past 50 years, with current GDP per capita sitting among the highest in the developed world, on par with rich economies such as the US, Denmark, Singapore and Sweden. Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic Australia enjoyed an impressive 28 year spell of uninterrupted economic growth. However we need to unpack the reasons behind this success to show how we have become complacent and potentially vulnerable to global changes.

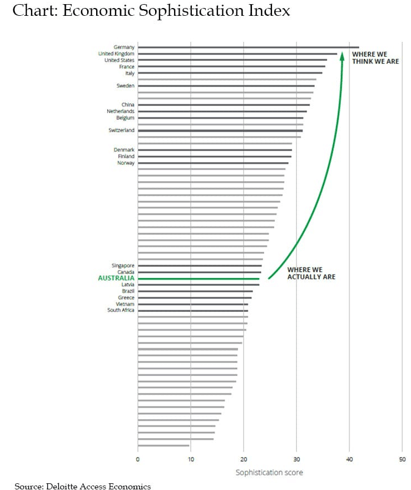

A recent report conducted by Deloitte Access Economics has summarised these issues through a sophistication index which ranks countries and their economies based on two measures: the value added to goods and services an economy currently produces; and how well connected the industries that make these products and services are in global supply chains. The productive knowledge or productive capabilities that an economy holds determine the frontiers of what they can produce and how much they can grow.

As you can see from the graph above Australia is ranked in 37th place on the world sophistication index, saying it is too reliant on mining and agriculture and is too vulnerable to any global shift towards renewable energy. This ranking is on par with the countries like Latvia, Brazil and Greece.

Deloitte have highlighted 5 key issues to understand the reasoning behind the poor rating.

- We are not as successful as an economy as we think we are. While GDP is high, our economy is not particularly complex and in fact can be seen to be quite fragile.

- We have relied on luck which has started to create complacency.

- We have neglected sectors with great future potential. Rather than taking a long-term view, Australia has focused on sectors like mineral resource and agriculture that have provided us with historical wealth.

- We are not well connected to the rest of the world. This can make it more challenging to improve economic complexity, especially with the recent rise of Asia on Australia`s doorstep.

- We are at the risk of the `tyranny of distance` again. With the world looking locally for supply chains, Australia is at risk because it is not engaging enough in the Asia Pacific region.

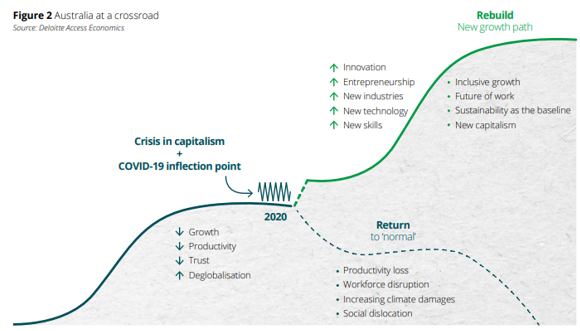

All of these points lead to a certain inflection point in the Australian economy and the pandemic has accelerated the time frame for this to occur.

Without diversification and innovation, an economy won’t be able to adapt quickly and absorb shocks. It must be noted that Australia has many of the building blocks to create new growth and improve resilience. This includes access to strategic minerals, renewable energy assets, proximity to the growth engine of Asia, successful agriculture exports, good education infrastructure and industry-leading digital technology.

But going forward Australia needs to move beyond these foundations to create a future-ready economy. Our challenge and our imperative is to find unique and differentiated ways to contribute to and connect with the globe.

There are seven opportunities highlighted that could promote Australia into the global economy to be more connected and find new opportunities for future growth.

- Feeding the world – Demand for Australian food is strong, but the core industries involved in Australian food production – agriculture, forestry and fishing are among the least sophisticated.

- Decarbonising the world – with competitive advantage in natural resources, technologies and energy, Australia can really take part in the move to global decarbonisation by producing new sustainable energy.

- Shaping the future of health – Australia can create new value by using technology to turn its world-class health research into implementable health and wellbeing solutions.

- Looking to the sky (and beyond) – Australia has a strong track record in the areas we have chosen to play in space, but also needs to grow its capabilities from niche research and manufacturing to end-to-end products and services

- Manufacturing the future – To play a greater role in global manufacturing, Australia should have a clear focus on moving up the value chain by connecting advanced manufacturing into areas of greatest economic opportunity

- Satisfying the senses – There is no ecosystem more agile and ever-changing than one that follows consumer demands. Australian organisations need to continue to be responsive and innovative by co-designing products and services

- Servicing the world’s businesses – Using virtual and digital technology, a significant opportunity exists to export B2B services such as engineering, telecommunications, professional services, and financial and insurance services.

If successful, our Index score could more than double, placing Australia above even the highest of performers. But this would require a drastic shift in the structure of our economy. We would need to increase our business services sectors, build greater balance and diversity in our trade relationships. If we were successful, we’d see our incomes rise and vulnerability to shocks fall. We’d be nimbler and better prepared to make the most of new opportunities.

Sources: Deloitte Access Economics